Alone, paralyzed and unable to utter a word.

Dezron Wesley of Brookhaven awoke to that reality after a third stroke sent him to a Jackson hospital on April 8.

Because of COVID-19, his wife, LaTonya Wesley, couldn’t be by his side during the hospitalization.

And the 48-year-old said it was frightening to be isolated and incommunicado. “I was at someone’s mercy,” he said.

“He told me how scary it was to wake up and not be able to talk or say what he needed,” said Taylor Miller, his speech therapist while at Methodist Rehabilitation Center in Jackson.

“People don’t think about how important speech is,” Wesley said. “I’d rather lose both arms and legs than not be able to talk. It’s more important to me than mobility.”

Wesley arrived at Methodist Rehab on April 24, and it was his second time to undergo stroke therapy there.

He’s more susceptible to multiple strokes due to Moyamoya Disease, a rare, cerebrovascular disorder caused by blocked arteries at the base of the brain.

Wesley could talk after his first stroke, so he admits he didn’t fully value speech therapy during his first admission. And it seemed he might still be in that mindset during his initial sessions with Miller.

“The first thing I understood him say was: ‘I hate speech therapy,’” Miller said.

In the rehab medicine setting, speech therapy addresses everything from swallowing issues to problems thinking, remembering and focusing. And Wesley thought tasks to address his cognitive issues were particularly tedious.

This time, though, he proved to be an enthusiastic patient. He knew how much he needed the help.

“When he first came, he was extremely weak, completely unintelligible, and could not produce any voice,” Miller said. “He also had the worst swallow I’ve ever seen.”

Wesley had dysphagia, a swallowing disorder that’s a frequent companion to stroke or brain injury.

Unlike people with a normal swallow, he could no longer sense when food was going into his airway. Without the cue to cough, he was at risk of aspirating food or liquids into his lungs and developing an infection. He had to rely on a feeding tube for nourishment.

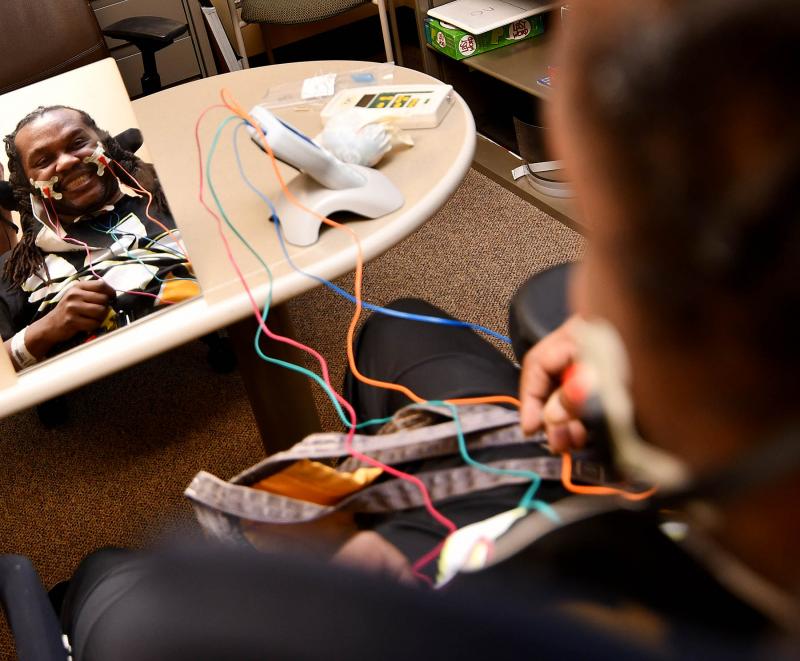

Using VitalStim—a device that employs neuromuscular electrical stimulation—Miller was able to re-educate and strengthen Wesley’s throat muscles. That therapy coupled with exercise and swallow maneuvers freed Wesley from the feeding tube.

“In three weeks, he went from pureed food to chopped meat, then to a regular diet,” Miller said.

Soon, he was filling up on favorites like fried chicken and Chinese food. “My wife was like: Where are you putting all that?’” he said.

As happy as he was to eat again—he’d lost over 20 pounds post-stroke—Wesley was more invested in regaining his voice.

Miller said he had significant damage to a few of his cranial nerves which severely impacted his speech (as well as swallowing). One was damage to his tenth cranial nerve, known as the Vagus nerve. Symptoms include difficulty speaking, a voice that is hoarse or wheezy, and trouble swallowing.

He also suffered from dysarthria, a motor speech disorder related to the nerve damage caused by his stroke.

“He had a difficult time forming words,” Miller said. “Everything sounded muffled, mumbled and strung together.”

Muscles in the face, lips, tongue and throat are all involved in talking, and Miller used a variety of strategies to strengthen and improve their coordination during Wesley’s therapy sessions.

For instance, using a device called the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument, Wesley did sets of what amounted to tongue pushups.

“Taylor has done her part and given me the tools I need,” he said. “I don’t know what I would have done without the techniques she has shown me. I am doing a lot better.”

It helped that Wesley made good on his goal to be “a willing participant.”

“He has been an absolute delight and made significant improvements,” Miller said. “He has come a long way.”

As he left MRC on June 9, Wesley had plans to continue therapy on an outpatient basis. The third stroke also left him paralyzed on his right side, and he hopes to recover enough to resume walking.

He also is determined to avoid another stroke, which he realizes will be a challenge because of Moyamoya.

Wesley said he felt defeated after his first stroke. “I was a wreck. I thought it was the end of the world.”

But his strategy now is to take every opportunity he can to get better. “I’m alive … so I have to make the best of it.”