The Research Study

To her long list of medical accomplishments, Jackson ob-gyn Dr. Freda McKissic Bush can now add celebrated research subject.

She recently became the subject of a scientific paper entitled: “Lazarus Effect of High Dose Corticosteroids in a Patient with West Nile Virus Encephalitis: A Coincidence or a Clue?”

Published in “Frontiers of Medicine,” the article is co-authored by neurologists Dr. Art Leis of Methodist Rehabilitation Center and Dr. David Sinclair of Mississippi Baptist Medical Center.

While Bush’s stunning recovery is the focus of the treatise, it’s a bit of poetic license to compare her experience with that of the Biblical Lazarus. She was not raised from the dead.

But the 71-year-old retired physician said she was “on my way out.”

“I was going to die, it was as simple as that,” she said.

Bush was suffering from West Nile virus encephalitis, a swelling of brain tissue that is one of three neuro-invasive forms of WNV infection.

In the years since WNV first arrived in the United States in 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended treating infections with only standard supportive care.

But during 16 years of studying neuro-invasive forms of the disease, Leis came to favor prescribing high-dose steroids for the most severe forms of the disease.

The approach seems to quell the body’s immune system attack of inflammation on healthy tissue. But Leis was cautious about using it at first. “It is counter-intuitive to weaken the immune system when a patient has encephalitis,” Leis said.

To be on the safe side, Leis initially delayed steroid treatment until at least two weeks from the onset of WNV. By 2018, he’d begun to rethink that timeline.

The CDC had found that WNV rapidly cleared the body in people with normal immune systems. And Leis’ own experiences with immune-suppressive treatments had not raised any red flags.

“To my knowledge we don’t have any cases where treatment with high-dose steroids initiated acute worsening that would suggest the virus had spread,” Leis said.

When he was consulted on Bush’s case in July 2018, Leis believed her condition demanded an aggressive approach, as did Sinclair.

“She was in the ICU in a semi-comatose state for a while,” Sinclair said. “It was very clear her whole brain was involved and the risk of disability at that point was extremely high—if not death.”

Leis and Sinclair say they sought to publicize Bush’s case because they believe scientific scrutiny of the approach is needed.

“We’re trying to look at deciding whether patients will improve spontaneously or if steroids are helpful,” Sinclair said. “This really needs to be studied in a manner where we have a control group who receives the current standard of care intervention.”

In the meantime, Leis will continue to contribute as a scientist who has long been on the front lines of WNV research.

In 2002, he and fellow MRC scientist Dr. Dobrivoje Stokic were the first in the world to link WNV to a polio-like paralysis. And over the years, MRC has been a valuable resource for physicians treating West Nile virus infection, as well as a support group site for survivors and their families.

Leis knows well the lifelong impact WNV infection can have. In his office is a five-drawer file cabinet full of patient data, as well as thank-you notes from people he’s helped.

“For those who have the more severe forms of West Nile virus infection, over half have persistent or delayed symptoms, such as severe, disabling fatigue, persistent headaches, sleep disruptions and trouble concentrating,” Leis said.

Some even experience disruption of their autonomic reflex system, which controls everything from blood pressure, cardiac rhythm, sweating, bowel and bladder control to gastrointestinal mobility.

Recently, Leis obtained disease-specific privileges at several metro Jackson hospitals, which will make it easier for him to consult with acute care physicians.

And Sinclair, for one, believes there’s no one better than Leis to help guide the care of WNV patients.

“I think I’m one of a dozen young neurologists in the state who look toward his expertise in the area of neuro-virology,” Sinclair said. “He has cared for the most West Nile virus patients and dealt with the most severe consequences of that illness. He’s someone I could turn to for advice on cases like that.”

Patient One: Dr. Freda Bush

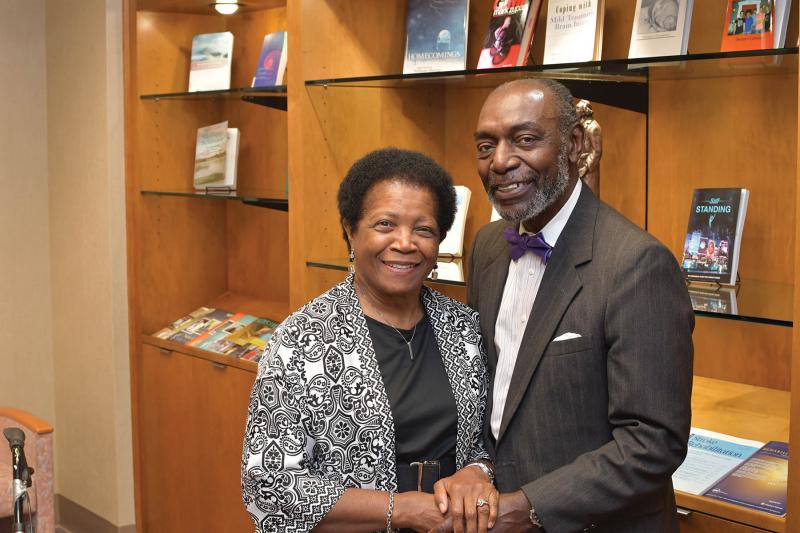

Like most long married couples, Lee and Freda McKissic Bush are deeply aware of each other’s moods.

So on the morning of July 17, 2018, Lee quickly realized something was amiss with his normally talkative wife.

The retired ob-gyn barely whispered yes or no to his questions. And she did not look well.

“I stopped getting ready for work and starting paying her attention,” he said. “Her torso was really burning up.”

After trying unsuccessfully to reach Freda’s doctor, Lee decided to rush her to the emergency room at Mississippi Baptist Medical Center in Jackson.

Much later she would ask him: “Why didn’t you call an ambulance?”

“Too slow,” he said.

Freda was well-known at Baptist, having delivered babies there since 1987. But when she arrived that morning, none of the staff had ever seen her like this—nearly unconscious and going downhill fast.

Her medical team quickly began a litany of tests. But it would be almost a week before Lee learned the source of his wife’s suffering.

She was diagnosed with West Nile virus encephalitis, a life-threatening form of the mosquito-borne disease.

What’s worse, Lee was being told the condition carried no treatment. “They said we’d have to wait and see what happens. And I said: ‘That’s my wife you’re talking about.’”

The couple had gotten married in 1969 after only three months of dating. In the years since, they’d reared four children, balanced two demanding careers and supported causes they believed in.

What loomed ahead was more opportunities to give back, as well as time to spend with their 11 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Surely, this wasn’t to be the end of a union between two people who’d shared so much—including the challenges of each growing up the fifth of nine children.

An engineer by training and a successful businessman, Lee went into problem-solving mode to save his wife.

“He took matters into his own hands and said: ‘Somebody has got to tell me something,’” Freda said.

After some networking, website searches and phone calls, Lee learned one of the nation’s foremost West Nile virus researchers worked just down the street at Methodist Rehabilitation Center.

Lee arranged a meeting with Dr. Art Leis, a senior scientist with MRC’s Center for Neuroscience and Neurological Recovery. And he’ll never forget seeing him for the first time.

“He walked into this huge waiting room at Baptist and I said: ‘Here comes my angel doctor.’ He said: ‘Angel? Why did you call me that?’ I said: ‘Because you are my angel.’ He said: ‘I don’t know if you know this, but my first name is Angel.’”

Leis advocated treating Freda with high-dose steroids, but he warned it could be risky.

“He said steroids will stop her brain from swelling, but it will also stop her immune system—which is kind of dangerous,” Lee said.

But Leis said he was willing to take the chance because he knew Lee would provide the close observation Freda would need during steroid therapy.

When anyone would urge Lee to leave his wife’s side for a well-deserved respite, he’d say: “I’ll leave when she leaves.”

“He made a decision that his job was taking care of me,” Freda said. “He wouldn’t go to work, and he slept in a chair.

“When I realized how much dedication he had given to me, I boohooed. I was overwhelmed. I tell people if I thought I loved him before, it doesn’t compare to now.”

As Freda began to regain consciousness, “she didn’t know who she was or where she was, but she was awake,” Lee said.

And he made it his mission to keep her roused. “I am playing spiritual music, dancing around and walking around her bed praying,” he said.

Baptist staff offered spiritual support, too. “Every doctor who came by said we’re praying for her,” Lee said. “They would pat me on the shoulder and leave out.”

The Bush’s adult children also came through for their parents. While their son took over for his dad at NCS Trash and Garbage, his three sisters rotated two-week caregiving shifts. And one of Freda’s sisters traveled from Washington, D.C., to lend a helping hand.

Freda spent three weeks at Baptist, including 15 days in ICU. Next came another 24 days at MRC, working on skills to regain her independence.

It wasn’t easy for the accomplished physician to acknowledge her deficits.

“I spent a lot of time crying,” she said. “I had already retired from medicine, but I was still very active. I was on a lot of boards and was working with the Medical Institute for Sexual Health in Austin. And to think now I couldn’t do anything, couldn’t even remember. I spent a lot of time crying because I wasn’t me.”

Lee, on the other hand, never lost hope.

“She is my miracle in slow motion,” he said. “The best thing for me was seeing in her eyes she was getting better and all the miracle steps in the right direction. When she could look at me and smile and say, I love you. Those were the nuances that kept me going.”

Today, Freda continues to progress. And while she’s chafing for more independence—she and Lee laugh that they never spent so much time together—she’s grateful for his commitment.

“I have to give credit to the Lord,” she said “He put us together, and he kept us together. I say I’m so sorry I got West Nile, but I’m so glad God gave me Lee Bush.”

Patient Two: Steve Tidwell

It’s small comfort now.

But Steve Tidwell of Madison believes he killed the mosquito that gave him a paralyzing case of West Nile virus poliomyelitis.

“I was outside working on the grill, and I remember when it stung me,” he said. “I remember seeing a big red butt full of blood, and I popped him.”

More than a year later, Tidwell is still dealing with the ramifications of that moment. It takes a brace on his left leg and a walker to move very far. But it sure beats where he started out.

“From the waist down, I had no movement,” said the union rep for the United Food and Commercial Workers. “And after 58 years of walking … that’s alarming.”

Tidwell said his illness began with achy legs and joints. At the doctor’s office, he tested negative for flu. But it was obvious something serious was afoot.

“When I got up off the bed, I collapsed,” Tidwell said. So his physician ordered tests for West Nile, Lyme Disease and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

“He said the tests usually take six days, and he would let me know. Meanwhile, I’m getting worse. That Friday, my son Weston helped me go to the bathroom and I collapsed again. My wife, Tracy, said we’re going to the ER. And they had to rig something up to get me in the car.”

The date was Aug. 24, 2018. “That was the last time he walked,” Tracy said.

Tidwell is fuzzy on the early details of his illness. “Tracy said I didn’t know where I was for two weeks,” he said.

But he does remember marveling at the cluster of IV bags hanging overhead. “I had two IV poles and both of them had about 30 things on them,” he said. “I guess they were steroids pumping in me.”

As he would learn later, Tidwell had arrived at Mississippi Baptist Medical Center in Jackson about a month after Dr. Freda Bush, a victim of WNV encephalitis. And her successful treatment with high-dose steroids became the protocol for his case, as well.

“His neurologist (Dr. David Sinclair) was amazing,” Tracy said. “He called it and started treating him immediately.”

“It may have stopped the process in its tracks,” Tidwell said. “Thank God it worked because some people (with WNV poliomyelitis) lose control of their bowels or urinary tract, and I did not.”

Sinclair’s treatment had been recommended by MRC neurologist Dr. Art Leis, a nationally recognized expert on WNV. So when time came for Tidwell to start therapy, MRC was the logical choice.

It became an even better decision when Tidwell learned his physical therapist would be a friend of his oldest son Mitch. “Chris McGuffey poked his head in my door and said, ‘I was hoping it wasn’t you,’” remembers Tidwell.

In Mississippi, patients with the most severe cases of WNV come to MRC for inpatient care. And while McGuffey was taken aback to see the disease affecting a friend, it didn’t make him go easy on Tidwell.

“If anything, I worked him harder,” McGuffey said. “And I wanted him to be as aggressive with me as he could without killing me,” Tidwell said.

Tidwell also got some welcome tough love from occupational therapist Debbie Webb. She was determined he’d go home as independent as possible. “Before I left, she made me get dressed and undressed by myself,” Tidwell said. “She said you are going to show me you can do this.”

Tidwell spent much of his therapy time strengthening his abdominal and back muscles. “Your core is vital and that is one of the areas that gets hit the hardest by West Nile virus,” McGuffey said.

Many WNV patients also struggle with crushing fatigue. “They get so tired, so quickly, you have to limit repetitions and allow more rest between them,” McGuffey said.

When Tidwell transferred to Methodist Outpatient Therapy in Ridgeland in September 2018, he still had a long road ahead of him.

“He came in with hardly any movement in his legs,” said Erin Perry, a physical therapist at the clinic. “And he still needed a little help with wheelchair transfers.”

Nevertheless, Perry was optimistic about his recovery. She left for maternity leave in March, and Tidwell remembers her saying: “You’re going to do something phenomenal while I’m gone.”

At the time, Perry had recently introduced Tidwell to aquatic therapy, which physical therapist Merry Claire Wardlaw continued in her absence.

Both say the pool workouts were a game-changer.

“That’s where he started to turn the corner,” Perry said. “He could do so much more in the water. He could move more freely without having to deal with gravity.”

Tidwell came to love his pool workouts, but he was initially hesitant to get in the water. “Think about it, I didn’t have legs,” he said. “But once I saw I wasn’t going to drown … I’d wear myself out in the pool because it was so much easier.”

While the therapists appreciated Tidwell’s workout ethic, they also had to temper his activities so he wouldn’t get too fatigued. “He’s the hardest working person to a fault,” Perry said. “He would have come to therapy every day if it was possible.”

“I’m not one to give up easy. I’m going to go at it hard,” Tidwell said. “I’m too active a person to be sitting on a couch.”

Tracy said her husband even manages to keep up with many of the chores on their 80-acre farm. “He still cuts the yard,” she said.

To move from his wheelchair to his zero-turn lawn mower, Tidwell built a transfer device from PVC pipe and a pool noodle. And to do exercises at home, he rigged up a Pilates-style machine using PVC pipe and a garage-door mechanism.

“If we do something here, he’s going to try to mimic it at home,” Perry said. “That’s how driven he is.”

Tidwell said he and his therapists have finally worked out a “happy medium” for his workout schedule.

And he’s proud of how far he’s come. “We made so much progress, I can walk 175 feet with a walker and a brace on my left leg,” he said.

And he has no doubt he can do more. “You won’t see me give up. T